How to Transform from Cost-Plus to Value-Based Pricing Culture

Published On 9 January, 2023

Cost-Plus pricing refers to the practice of setting a percentage markup on system costs to determine a list price or net invoice price to customers. It is a simple and effective way to set a price quickly and be confident that your input costs will be covered. However, cost-plus pricing has several critical limitations, which can cause several significant impacts on profitability.

Firstly, cost-plus pricing fails to identify the potential price that could be realised in the market for each unique customer. Blanket mark-ups on cost, in many cases, are not a proxy way to determine a product’s value and sell price in the market.

Secondly, cost-plus pricing can result in over-pricing, leading to lost sales volume and poor customer perceptions in the marketplace that could damage the brand of the product or the company.

In summary, cost-plus pricing puts a business at risk of under-pricing and thereby losing margin potential or over-pricing, thereby losing revenue and contribution margin to profitability in addition to longer-term brand equity risk.

When Cost-Plus Goes Wrong: Case Example

A large corporate stationary supplier had engaged a Procurement Manager to negotiate lower purchase prices from suppliers. The Procurement Manager was successful in obtaining cost reductions of 5-20% on high-volume standard products purchased by most customers of this stationery company.

Once the new costs had been agreed upon, they were entered into the ERP system as new standard product costs. Inexperienced sales analysts began seeing margins for products like writing instruments with gross margins of 50% instead of the usual 40%.

The sales analysts, in conjunction with the sales managers, began discounting the writing instruments, believing that the market could only stand margins up to 40%, not realising that the margins were the result of lowered costs, not price increases.

Effectively, all the additional profit gains negotiated by their Procurement Manager were dissipated over 3-6 months as the sales teams and their data analysts reset prices lower to align with their expectations of selling products at a 40% margin. Eventually, this mistake was discovered during a pricing improvement project and steps were taken to reduce discretionary discounting to regain some of the lost margins.

When is a good time to migrate, and who should be involved?

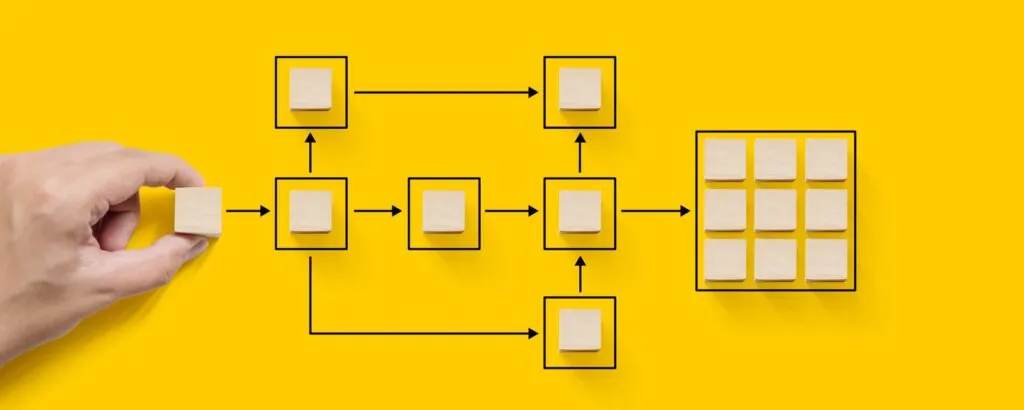

Migrating from cost-plus to value-based pricing requires engagement and alignment across sales, marketing, finance, operations, and the Executive Team. There are several catalysts to select a suitable transition time for your business:

- Implementation of a new ERP / WMS system (e.g., SAP, ORACLE)

- Introduction of a new product range or upgrades to existing products

- Implementation of a price increase because of inflation

Of course, you don’t need to wait for any of these three catalysts to be in play to commence migration towards value-based pricing.

Engaging all stakeholders in developing a new value-based pricing strategy and architecture is essential. This can be achieved through the distribution of discussion papers, planning workshops, and test-and-learn pilot programs to build evidence and the business case for change.

How do we migrate to a value-based pricing culture?

To migrate, you must undertake customer interviews to identify problem sets, pain points, goals, and aspirations for each customer type. Then identify what assets (physical or intellectual property), processes, infrastructure or other human resources are available to solve these customer problems or deliver benefits to support the customer’s goals and objectives.

It is important to identify how your value driver set differs from the customer’s current solution and the economic value your solution creates vs. the alternative. The economic value may be determined through estimation, financial modelling, or feedback from the customer.

Once this value has been defined, it must be communicated to the appropriate personas within the customer’s company. What is valuable to the CFO may not be as valuable to the Operations Director. In addition, the value may need to be communicated to your customer’s customer. In B2B environments, your customer’s customer significantly impacts your perceived value and pricing power. It is crucial to develop marketing collateral that communicates value to your immediate and downstream customers in the channel.

Value Definitions

Value can be generated for customers in many ways and across several dimensions. For example, value can be generated by having a product with tangible qualities superior to competitors. The features of this product enable your customer to sell their products and services at a higher price or reduce their need to replace an item more frequently.

Value can also be generated through non-product factors such as the transactional elements of the purchase, such as those found in the supply chain, including short lead times, the ability to manage highly volatile demand spikes, logistics network to allow product to be supplied across the country and electronic transactions and tracking systems to manage forecasting and customer expectations.

Customers are willing to pay premiums to avoid problems for accelerated levels of service, faster delivery times, the certainty of supply, and technical support when unexpected situations arise. Customers will also pay substantial premiums for risk mitigations and warranties. Suppliers with redundancy built into their manufacturing capacity and supply chains carry the extra cost of operations burdens, but select customers can highly value these capabilities.

Simple steps to develop a pricing strategy.

Reviewing your pricing strategy and architecture is important in migrating to a value pricing culture.One of the simplest ways to develop your pricing strategy is to ask your sales and marketing teams the following questions:

- Who is our core target market?

- What are the primary problems and pain points our target market experiences?

- What is the economic and psychological cost if these problems still need to be solved for the target market?

- If our business was a brand of motor vehicle, what brand would it be? For example, are we Hyundai, Toyota, BMW, or Rolls Royce?

- Given our positioning in the market, what approach will we take to the development of our revenue model (how we charge customers), the discounting tactics that we employ (depth, duration, frequency, and mechanics), and the media we will use to communicate our value to our target market.

Designing the right pricing architecture

In moving from cost-plus to value-based pricing, reviewing and redesigning your price architecture is critical. In many B2B companies, price architecture refers to the list price, customer discount and rebate mechanisms established to generate invoice prices and net prices to customers.

In many cases, the list price per material item or SKU, are often generated by a simple mark-up percentage on system cost that, in many cases, is heavily inflated to accommodate generous discounts of 50-70% off the list price. Often, the cost differential between many items is negligible, resulting in a list price identical for many items; however, one item is often more highly valued than the others.

By evaluating your SKUs through the lens of value to the customer, it is possible to increase the list price of the more valuable SKUs to capture margin opportunities. Conversely, highly competitive SKUs under intense price pressure can be reduced in list price to make them more competitive, maintain sales volume, and drive customer share of wallet opportunities.

Risks during the transformation process

The most common risk exposure that a business has in changing its pricing strategy is that not every team member is aligned to the strategy and continues to approach pricing in the same way that they have undertaken previously, thereby putting their pricing at odds with the new pricing strategy. This may have the undesired effect of destabilising market prices through channel conflict, resulting in unpredictable marketplace behaviours and margin erosion throughout the supply chain.

A second risk is poor implementation of new price architecture into an ERP system, resulting in incorrect invoicing. Individuals may attempt to amend list prices to align with their own perception of market price acceptability. These changes may be inconsistent with the strategy that has been agreed upon to support market positioning and value proposition.

A third risk is that a new price architecture is implemented without the appropriate policies, controls, and guide rails, leading to price overrides, excessive discounting, and margin erosion.

To combat these risks, it is critical to ensure all staff understand the company’s pricing strategy and market positioning and are clear on their roles and responsibilities to support pricing strategy, structure, and operations within the business.

Pricing University can educate your teams to employ a common value-based pricing language to identify value pricing opportunities and support the transformation of the company culture away from cost-plus pricing compliance and towards a culture of value-based pricing commitment